The Illegal Coal Miners of Ukraine's Donbas

This reportage documents the profound devastation left in the wake of industrial collapse, particularly when it cripples a dependent economy. Ukraine's ability to import coal more cheaply than it can produce might seem economically sound to Kyiv politicians, who view sacrificing inefficient, subsidized mines as a small cost for economic stimulus. Yet, for the miners and their families in the Donbas, these closures have unleashed a social and economic catastrophe. Plagued by unprecedented unemployment and pervasive hunger, many—including children as young as 11—have been forced into dangerous work in mafia-controlled illegal mines.

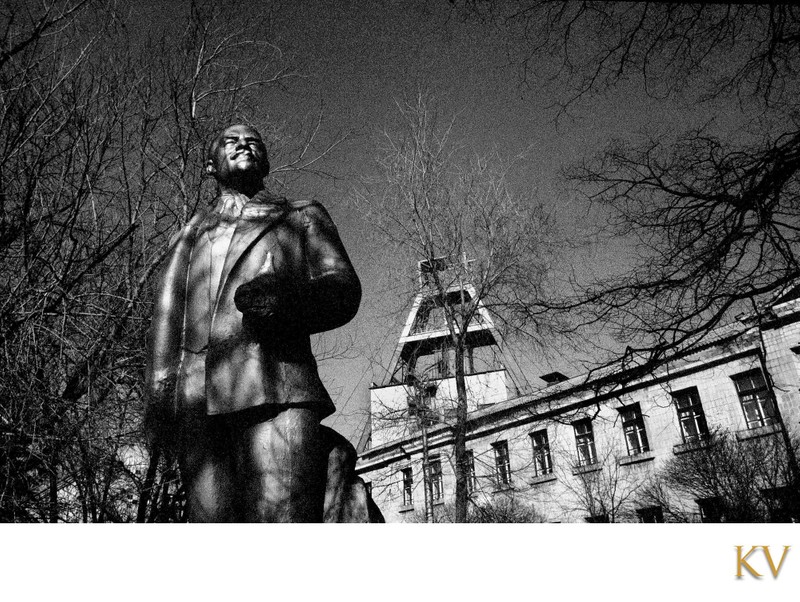

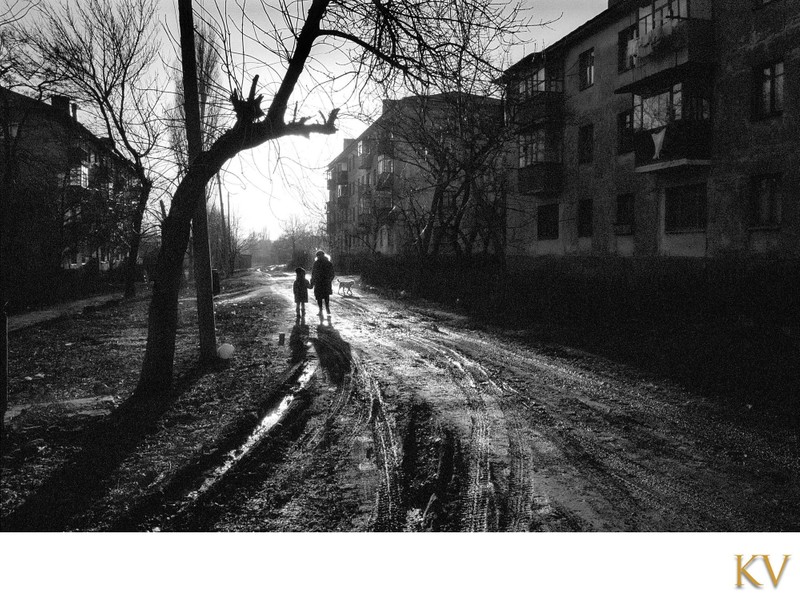

Snezhnoye was once the model of Josef Stalin's planned cities. Its industries, including metallurgy and chemical plants, were directly dependent on the local mines for fuel and raw materials. In 1997, when the World Bank began closing the mines, the economy collapsed. With factories, schools, restaurants, and shops going out of business, unemployment soared 50%. A population previously at 100,000 fell to 60,000 in less than 10-years. For many desperate people, illegal mining provides their only hope of feeding their families.

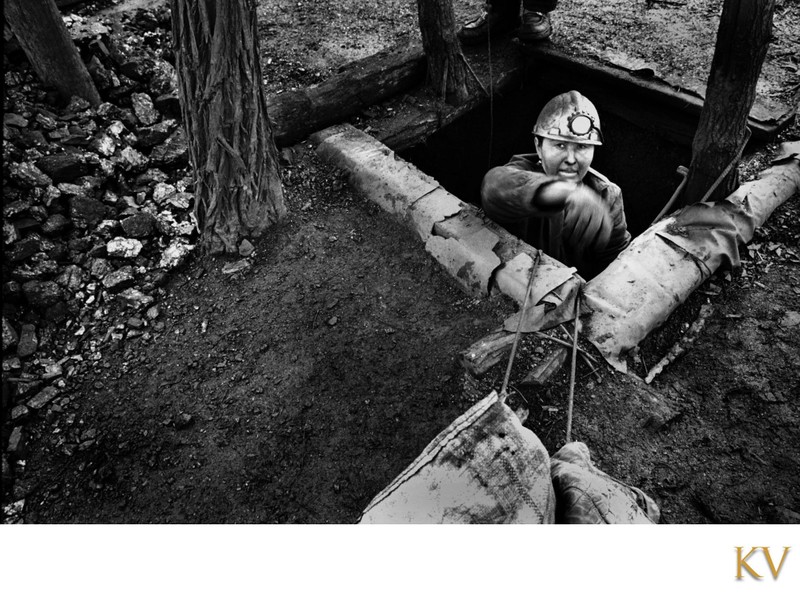

Natasha, 40, must work 12-hour shifts with a quota of two tons of coal each month to work on the gang. She receives $29 a ton. Angered by the deaths of both her husband and father to the mines, she states: “If we don’t work, we don’t eat. Just last month, a woman near us died from the cold because she couldn't afford to buy coal.”

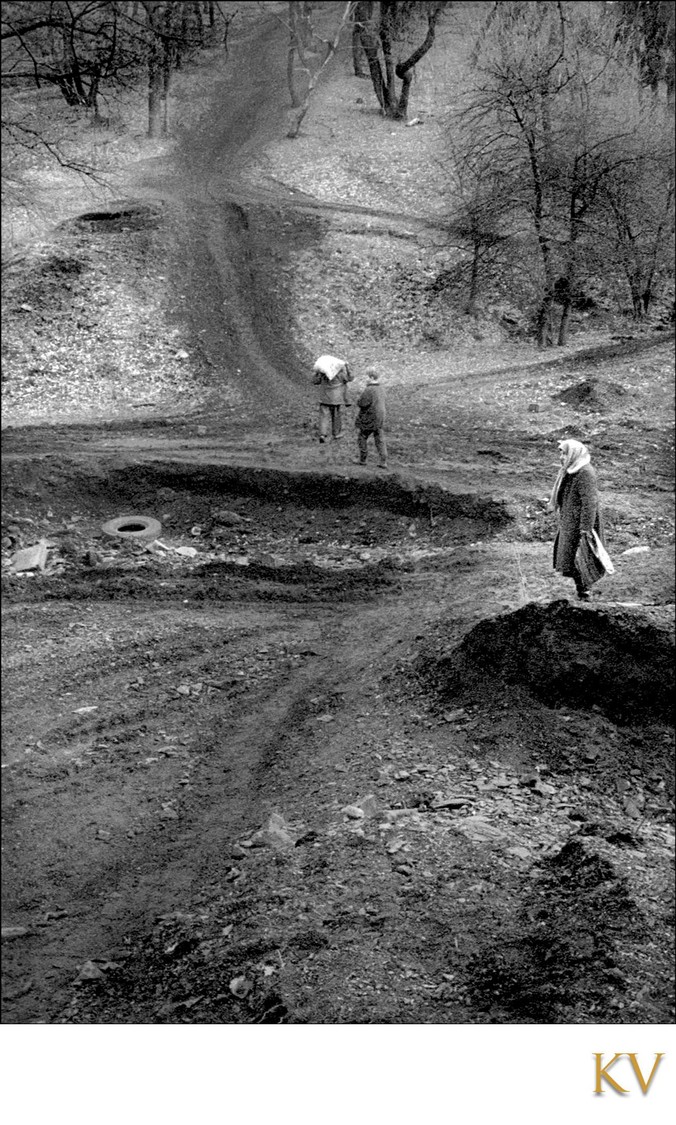

An elderly woman searches for coal to heat her home as two 16-year olds take turns carrying a 100-pound sack. Each sack of coal brings just $1.50 on the black market. The human toll is much costlier as the mines have claimed two of these boys friends in the past year alone.

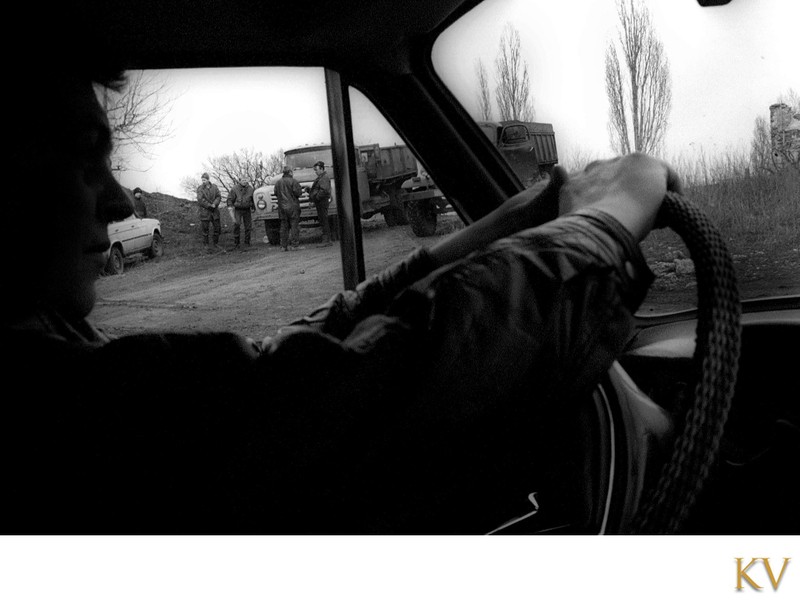

Members of the local mafia wait for the miners to bring them their coal. As the mafia grows stronger and more powerful on the backs of the miners and their families, politicians are less inclined to admit that illegal mining exists. Punishment of murder, violence and extortion are meted out to those who disparage the operations or speak to journalists.

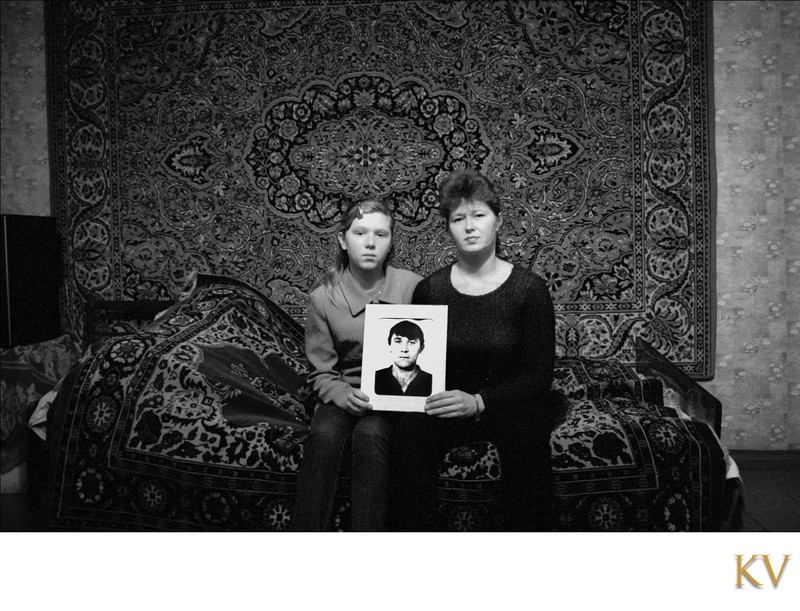

Valentine 64, and Valentina, 62, contemplate the future for their 10-year-old granddaughter. “She will either be forced into illegal mining or worse – the sex trade,” states Valentine. The ‘Natasha Trade’ is a real concern as over 120,000 young Ukrainian women were trafficked last year. With no jobs and no future desperate women in Snezhnoye like their counterparts throughout the Ukraine fall prey to the traffickers’ promises.

Kurt Vinion Reportage Portfoilo